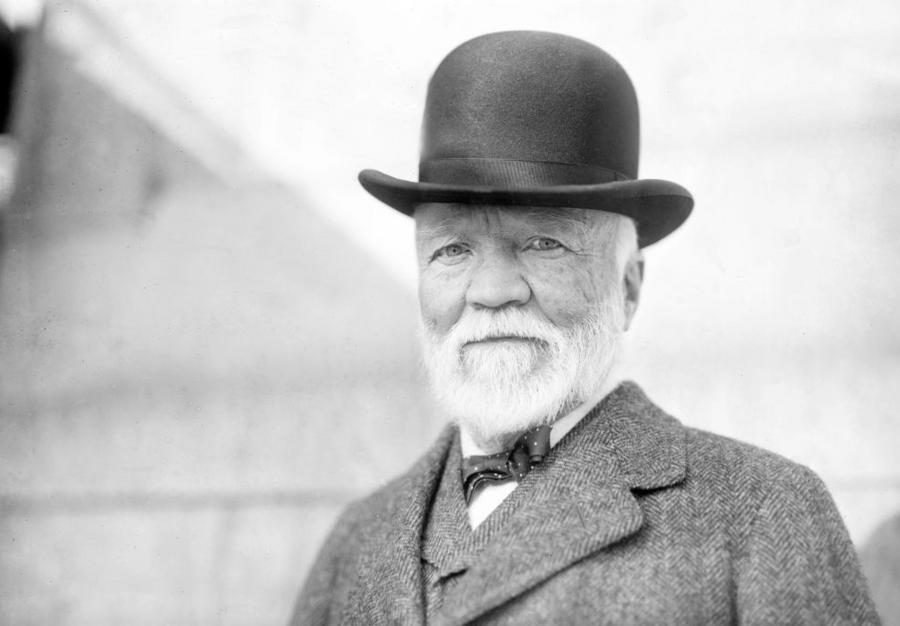

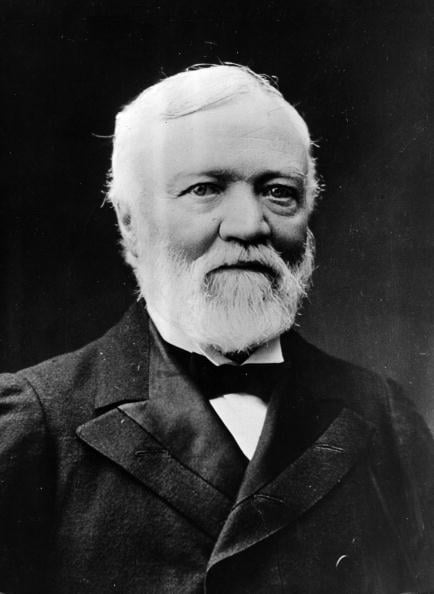

What was Andrew Carnegie's net worth?

Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish-American industrialist who led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century. During his lifetime, Andrew Carnegie had a peak, inflation-adjusted, net worth of $310 billion. That's enough to make him the 4th richest human being of all time. Andrew Carnegie is one of the most generous philanthropists in human history, having donated over 90% of his fortune to various foundations, charities, and organizations before his death.

He is credited with expanding the American steel industry in the 19th century by mass-producing steel and implementing vertical integration of steel production. At his peak, Andrew controlled the most extensive integrated iron and steel operations ever owned by an individual in the United States. One of his two great innovations was the cheap and efficient mass production of steel by adopting and adapting the Bessemer process for steelmaking.

In 1909, he sold his company, the Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Steel Company, to J.P. Morgan for $303 million. His share of the sale was $225 million, which is the same as roughly $7 billion in today's dollars. The final amount eventually ballooned to $480 million thanks to the interest paid on the bonds Morgan used to secure the transaction. Carnegie's wealth, in comparison to US GDP at the time, means his personal fortune is equal to hundreds of billions today. Most estimates peg his current-day equivalent net worth at $300-$310 billion.

The renamed U.S. Steel Corporation would soon become the first company in US history to have a market cap north of $1 billion. Carnegie devoted the remainder of his life to large-scale philanthropy, with special emphasis on local libraries, world peace, education, and scientific research.

Before his death, he had already given away more than $350 million of his personal fortune. At his death, his last $30,000,000 was given away to foundations, charities, and to pensioners.

Early Life

Carnegie was born on November 25th, 1835, in Dunfermline, Scotland, to parents Margaret and William Carnegie. His upbringing was extremely modest. The family lived in a two-room cottage. The entire first floor of the cottage was his father, William Carnegie's workroom for weaving fine cloths. The family lived entirely in a single room upper floor. His mother helped supplement the family's income by selling potted meats. After struggling to make ends meet in Scotland, the family borrowed money from Margaret's brother, George Lauder, Sr., and moved to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in the United States in 1848.

After moving to the United States, Carnegie began working as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill. He then became a telegraph messenger boy in the Pittsburgh office of the Ohio Telegraph Company. His transition to working at the Pennsylvania Railroad Company when he was 18 would prove to be instrumental in his career, as his work ethic was quickly noticed, and he was eventually asked to become the superintendent of the Western Division. The connections he made while working in the railroad industry were very helpful to Carnegie later on, as he met many future investors during this time and became an adept manager.

Andrew's business interests resulted in his first $10 dividend check, which he received in 1866. The 21-year-old would later describe the feeling he got from that check:

"It gave me the first penny of revenue from capital – something I had not worked for with the sweat of my brow. Eureka! Here's the goose that lays the Golden eggs!"

Dividend checks and interest payments on bonds would propel the young industrialist into a millionaire before he was 40.

Professional Pursuits

For the first few years of the Civil War, Carnegie received a deferment from the draft because his work for the Pennsylvania Railroad was considered essential to the war effort. Pennsylvania's production of munitions, building materials, and coal was a lifeline for the Northern army, and the state's railroads were crucial supply arteries up and down the East Coast for both goods and troops. Carnegie's deferment eventually expired, but he was able to pay an Irish immigrant $750 to serve in his place. This practice was not illegal and was common for wealthy industrialists of the time.

When the war ended, Carnegie continued developing his skills as a manager and investor. He arranged a merger between a sleeping car company and the inventor of a sleeping car for first-class travel, that proved to be successful for all interested parties.

Carnegie was also such a formidable force, even in his early 30s, that lucrative business opportunities frequently found their way to his desk from new outfits that wanted him as a partner rather than a future competitor.

A hallmark of Carnegie's pre-steel success was marrying his current business interests with related industries using sometimes less-than-ethical practices. For example, owning a majority stake in an ironworks company that just happened to be chosen as the primary supplier of iron to the railroad in which he was a major investor. Or using inside knowledge of where future railroad tracks would be laid to buy up real estate in areas where future towns would almost certainly spring up. Insider trading would not be made illegal until 1934, so this was considered fairly standard business practice at the time. Carnegie took this strategy to extreme heights in the 1860s and 1870s.

In another famous example, in 1867, Carnegie established a company called the Keystone Telegraph Company. He gave himself the majority ownership and distributed a few percentages to partners. He also arbitrarily valued the company at $50,000. It had no assets or contracts at its formation. It soon earned a contract from the Pennsylvania Railroad, where Carnegie was still a major investor, to lay telegraph lines along its tracks. Six months after forming the company – before any telegraph line had actually been laid – Carnegie sold the Keystone Telegraph Company to the Pacific & Atlantic Telegraph Company for 6,000 shares of its stock, which at the time of transaction were worth $150,000. A 3x return in six months, essentially on a hypothetical company. Within a few years, his old partners from the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired control of P&A Telegraph. In that transaction, Carnegie was paid in shares of Western Union. He held those Western Union shares for the rest of his life, earning lucrative annual dividends.

By the early 1870s, Carnegie's major interests were:

- 40% of Union Iron Mills (also known as Carnegie, Kloman & Co)

- 20% of Keystone Bridge Company

- 40% of a furnace company called Lucy

- Large holdings of several publicly-traded railroad companies, notably the Pennsylvania Railroad

To raise money for his ventures, Andrew spent significant stretches of time traveling in Europe selling bonds. When he wasn't selling bonds, he was dealing with iron and steel supply shortages that made building bridges and railroads extremely stressful.

(Photo by APIC/Getty Images)

Steel

Carnegie's interest in the railroad industry soon shifted to ironworks and steel, the industry in which he would ultimately make his fortune. Carnegie's impact on the steel industry was lasting and helped accelerate the growth of U.S. steel to exceed that of the U.K. Two main factors were instrumental in this growth – Carnegie's decision to adopt the Bessemer process, ultimately resulting in a drop in steel prices and vertical integration of the steel industry. Carnegie worked to establish control over the suppliers of all the raw materials needed to produce steel, purchasing rival companies to launch the Carnegie Steel Company then.

Sale to J.P Morgan

As Carnegie neared retirement in the early 1900s, a Carnegie Steel executive named Charles M. Schwab began secretly negotiating to sell the company to financier John Pierpont Morgan, better known by the name J.P. Morgan. Schwab is not related to today's Charles Schwab financier, but the bank J.P. Morgan is indeed directly related to this same financier.

A deal was eventually struck where Carnegie Steel was sold to Morgan for $303 million. Carnegie's share of the profit amounted to over $225 million dollars. The resulting company, which Schwab ran, was named the United States Steel Corporation.

J.P. Morgan did not have $303 million in cash to physically pay for the deal. The payment was made in bonds – physical paper bonds that paid 5% annual interest over 50 years. The bonds were delivered to a bank in Hoboken, New Jersey, where they were housed in a vault that was custom-built to house the collection. With interest, the total cost for the acquisition eventually grew to $480 million.

One of his first acts after cashing out was to transfer $5 million to fully fund his steel workers' pension.

Philanthropic and Scholarly Pursuits

Throughout Carnegie's career in business, he also was devoted to writing and started getting involved with philanthropy. He donated money towards the establishment of the Dunfermline Carnegie Library back in his hometown in Scotland and helped establish what is now the Carnegie Laboratory at NYU. He also was a regular contributor to several magazines, such as "The Nineteenth Century" and "North American Review."

Carnegie also published several books, most famously including "Triumphant Democracy" and "Wealth." He wrote at length about the American system of government as well as his philosophy regarding the duties of the wealthy in the distribution of their wealth.

Upon retirement, Carnegie became a full-time philanthropist. He was instrumental in the establishment of the public library system in the U.S., Canada, and other English-speaking countries, helping fund and build over 3,000 libraries.

Getty Images

He also was an education advocate, investing heavily in many universities, research centers, and other education organizations throughout his latter years, both in the United States and abroad. He donated $10 million to George Ellery Hale in order to help him build the 100-inch Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson, which ultimately was a successful project. He also established the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland with the goal of improving scientific research opportunities at Scottish universities. Carnegie also supported Booker T. Washington in his effort to improve education for African-Americans, helping him create the National Negro Business League.

In addition to education, Carnegie was also very interested in music, leading him to personally fund the construction of Carnegie Hall in New York City, as well as the construction of over 7,000 church organs around the world.

Personal Life

At the age of 51, Carnegie married Louise Whitfield, who was 30 at the time. The couple married in New York City and had their only child, a daughter named Margaret, together ten years later. Carnegie died in 1919 in Massachusetts of bronchial pneumonia.

Legacy

Carnegie lives on in the many foundations, organizations, universities, and charities that he either founded or made significant donations to. At the time of his death, he had already given away over $350 million dollars, and his remaining estate was donated when he died.

Among many, some of Carnegie's most notable legacies include Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, which Carnegie originally founded as the Carnegie Technical Schools, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Additionally, a number of streets, towns, and awards have been named in his honor, including the Carnegie Medal, a UK children's literary award, the towns of Carnegie, Oklahoma and Carnegie, Pennsylvania, and Carnegie Hall in New York City.

/2021/03/Andrew-Carnegie.jpg)

/2020/09/John-Pierpont-Morgan.jpg)

/2023/02/David-Tepper.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2009/09/donald.jpg)

/2014/06/george-hearst.jpg)

/2014/01/corn.jpg)

/2014/09/Manoj-Kumar.jpg)

/2012/12/Jeanine-Pirro.jpg)

/2023/10/Robert-Irwin.jpg)

/2019/02/Sam-Seder.jpg)

/2020/07/patti.png)

/2010/03/GettyImages-911943150.jpg)

/2011/08/Troy-Landry-1.jpg)

/2010/03/lf2.jpg)

/2010/03/GettyImages-146012097.jpg)

/2014/06/GettyImages-855956732.jpg)

/2013/03/Damon-Wayans-Jr-1.jpg)

/2021/03/Andrew-Carnegie.jpg)

/2014/01/corn.jpg)

/2014/09/John-D.-Rockefeller.jpg)

/2020/09/John-Pierpont-Morgan.jpg)

/2020/03/john-d-rockefeller-1.jpg)

/2015/09/charles-m-schwab-10.jpg)

/2018/02/gw.jpg)

/2015/05/thumb6.jpg)