The New York Knicks are always an interesting spectacle. Last season alone, their star player got into a public feud with the team president, another player disappeared and missed a game, and their star of the future skipped out on his exit interview.

Perhaps we shouldn't be too surprised, though. After all, the Knicks have made a habit out of this sort of thing, especially when it comes to paying people to go away.

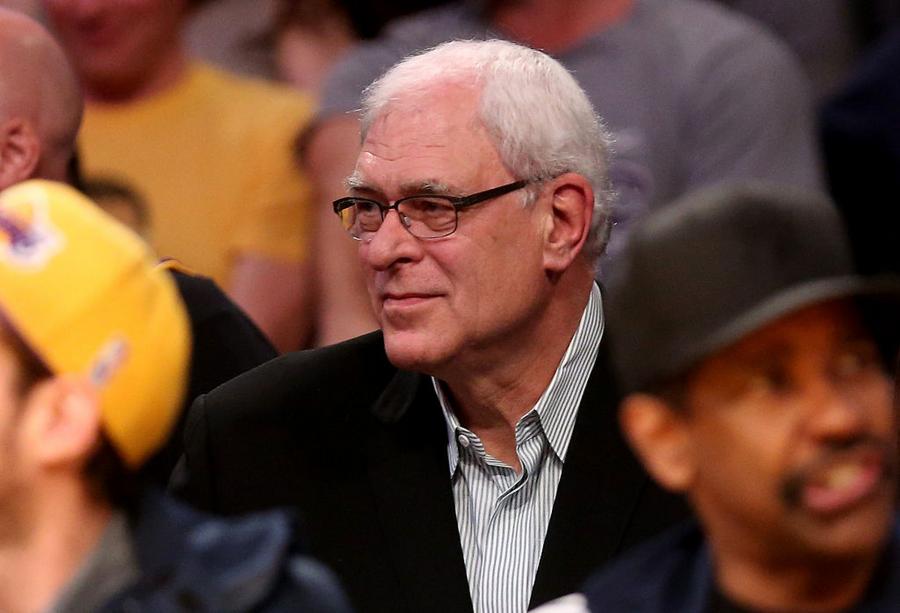

The most recent example of this is Phil Jackson. Knicks owner James Dolan signed Jackson to a five-year contract that paid him $12 million per year, the most any executive has ever made. However, after about 3.25 years and a 90-171 record, Jackson and the Knicks agreed to part ways.

Jackson had already picked up his option for the final two years of his deal, though, so the Knicks will be paying him a total of $20.5 million to stay far, far away from the franchise.

Stephen Dunn/Getty Images

Jackson is hardly the only person to whom the Knicks have given dead money. Back in 2005, the team signed head coach Larry Brown to a five-year, $51 million deal. The Knicks went 23-59, their worst record in franchise history, and Brown was fired. He sought to get the remaining $41 million of his contract – plus $12.5 million in damages – but eventually settled for $18.5 million.

That severance pay, combined with his first-year salary, means Brown made $28.5 million during his lone year in New York. Or, to put it another way, he made more than $1.23 million per victory.

Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

Maybe the biggest debacle, though, is guard Allan Houston. In 2001, triple-digit contracts were a rarity, but that didn't stop the Knicks from signing Houston to a six-year deal for $100 million. Houston was hurt for the final three years of his deal and played his final game for the franchise on January 19, 2005.

Of course, even though Houston wasn't on the court, he was still making money. He missed the remainder of the 2004-05 season and the entire 2005-06 season, collecting a little less than $32.4 million without playing a single additional game.

Ezra O. Shaw/Allsport

In fact, Houston's deal was so bad that the NBA changed its collective bargaining agreement to avoid situations like his in the future. The provision, officially called the amnesty clause but affectionately known as the "Allan Houston Rule," allows teams to release a player without his contract counting against the luxury tax. The player still gets paid and his contract is part of the team's salary, but it can save teams who are in danger of hitting the luxury tax.

Despite the clever name, the Knicks didn't actually use their exception on Houston, but rather on forward Jerome Williams. The Knicks correctly predicted Houston would retire; insurance covered most of the payments he was due, and his salary didn't count towards the luxury tax because he retired due to injury.

Compared to the rest of the century, it's one of the best moves the Knicks have made.

/2016/07/GettyImages-466436678.jpg)

/2017/09/GettyImages-667847096.jpg)

/2017/01/GettyImages-143968989.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-632591210.jpg)

/2020/04/GettyImages-53180864.jpg)

/2018/12/GettyImages-823594306.jpg)

/2022/06/paul-.jpg)

/2015/08/Fiona-Bruce.jpg)

/2012/08/Linda-Hogan-1.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2012/10/Nick-Hogan.jpg)

/2010/12/Brooke-Hogan-1.jpg)

/2010/12/Antoine-Walker.jpg)

/2022/11/burt.png)

/2020/07/brian-austin-green.jpg)

/2011/05/Mary-Hart.jpg)

/2020/02/Jaclyn-Smith.jpg)

/2020/12/selena.jpg)

/2010/11/Joan-Baez.jpg)

/2016/02/GettyImages-502028086.jpg)

/2010/01/Judd-Apatow.jpg)

/2021/01/Richard-Marx.jpg)

/2015/03/GettyImages-908573706.jpg)