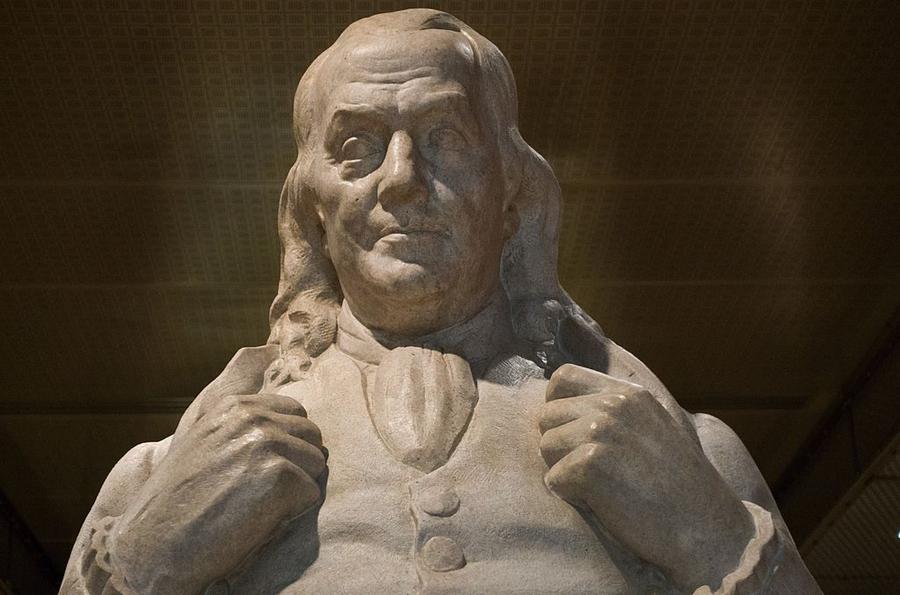

Imagine not being able to touch an inheritance for the foreseeable future. Well, in April of 1990, on the 200th anniversary of the death of Benjamin Franklin, the cities of Boston and Philadelphia became beneficiaries of Franklin's 18th century wisdom.

Franklin left the two cities a sum of $2,000 sterling. There was just one catch: Some of the balance could not be used for 100 years, and the remainder could not be drawn on for 200 years.

The founding father was born in Boston in 1706 and moved to Philadelphia when he was 17. In his Will, he set aside $2,000 to be divided between Boston and Philadelphia. The money was to be used as loans for young apprentices. He hoped this would help young tradesmen get started in their jobs.

Paul J. Richards/AFP/Getty Images

His instructions also stated that after the 200 year timeline, 26 percent of Boston's remaining balance would go to the city and 74 percent would go to Massachusetts.

In the late 90s, Boston's trust balance was $4.5 million, while the Philadelphia account was valued at $2 million. The large value difference was due to better investment handling in Boston.

And the $2,000 sum was significant: This was the salary Franklin earned while serving his term as Governor of Pennsylvania from 1785 to 1788. "It was one of Franklin's favorite notions, one he tried to get written into the Constitution, that public servants in a democracy should not be paid," said historian Whitfield Bell, who is the curator of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.

So how would the money be allocated two centuries later?

Staying true to Franklin's vision, Bell headed a committee that made the decision to use the city's share—approximately $520,000—as grants for high school graduates going on to learn a craft or trade.

The other decisions were not made as easily. The Pennsylvania State Senate passed a bill to donate all of its share—$1.5 million—to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, a museum built partly with money from the trust on the 100th anniversary of Franklin's death. The State House of Representatives was wary of this plan.

Former Massachusetts Attorney General James M. Shannon added, "It's a wonderful irony that 18th century money should become available just when we need it for our problems today."

Massachusetts contemplated using the money for low-income housing, give it all to a university, or, like Philadelphia, stay true to Franklin's original purpose and provide scholarships for students studying a trade.

Even in the 18th century, Franklin suspected there may be conflict, writing in his will: "Considering the accidents to which all human affairs and projects are subject in such a length of time, I have perhaps too much flattered myself with a vain fancy that these dispositions will be continued without interruption and have the effects proposed."

/2019/05/bf.jpg)

/2018/02/gw.jpg)

/2017/07/GettyImages-80729269.jpg)

/2017/04/GettyImages-630604934.jpg)

/2017/06/Carl-Icahn.jpg)

/2015/01/bridge.jpg)

/2014/12/steve-mcmichael.png)

/2018/11/Dick-Durbin.jpg)

/2010/03/Chad-Hurley-e1739058448898.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2021/09/steve-chen.jpg)

/2022/05/Peter-Doocy-1.jpg)

/2015/07/Edwin-McCain-1.jpg)

/2018/03/chuck2.jpg)

/2020/06/john-goodman.jpg)

/2013/11/jw-1-e1718208295517.jpg)

/2020/05/Kayleigh-McEnany.jpg)

/2020/03/carlos-santana.png)

/2020/02/roseanne.jpg)

/2020/11/tina.jpg)

/2010/12/Jayson-Werth.jpg)

/2010/01/Shannon-Sharpe.jpg)

/2020/06/Tommy-Chong.jpg)