We know about the Rockefellers and Carnegies. We know about the enterprising families who built modern America. Except for one – the Clarks. Andrew Carnegie had a theory that life should be divided into three stages: education, making money, and giving all the money away. Towns across the U.S. still have Carnegie libraries, schools, and public endowments. New York's Rockefeller Center and the Rockefeller Foundation carry on that family's name and philanthropic missions. But what of the William A. Clark and generations of Clarks who have followed? Never heard of William A. Clark? Well, consider the following:

• In 1858, the warships HMS Agamemnon and USS Niagara made the first transatlantic telegraph cable.

• In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone.

• In 1879, Thomas Edison created the first commercially practical incandescent light bulb.

• In 1882, Switzerland's Edward Ruben invented the full metal jacket bullet, which increased the distance one could stand from another person while killing him (or her).

None of these advancements during the Industrial Revolution would have been possible without copper provided by W.A. Clark. So why, throughout history, has this man's achievements and this family's contribution been lost to the annals of time? Why aren't the Clarks as celebrated as the Rockefellers, Carnegies, Astors, Vanderbilts, and Whitneys?

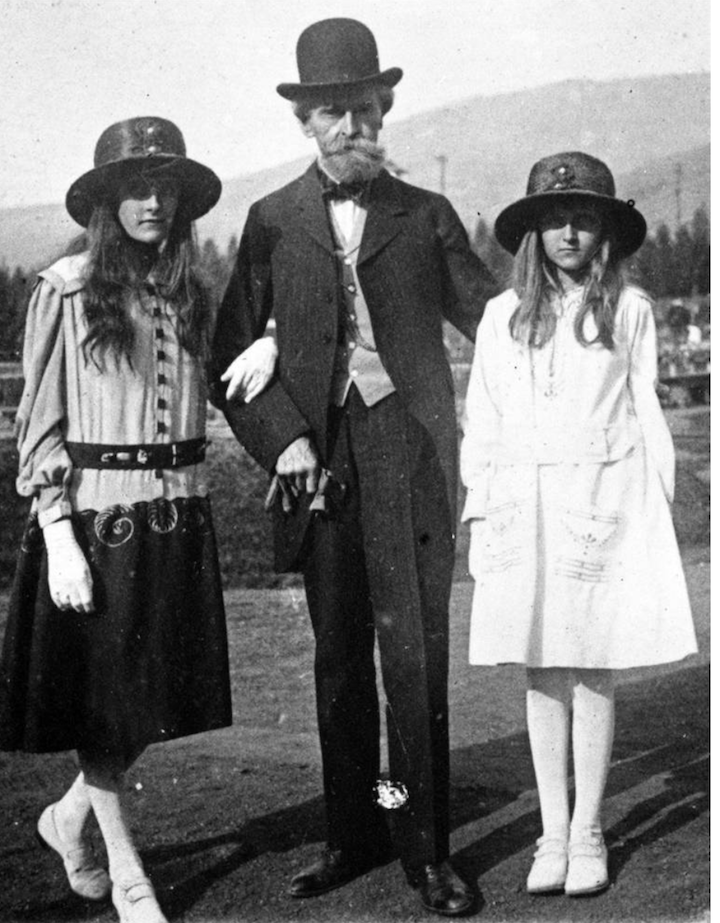

Photo via the Montana Historical Society/Wikimedia Creative Commons

W.A. Clark made his fortune largely in copper mining. When he died on March 2, 1925, leaving behind a wife, young daughter, and grown children from his first marriage, his net worth was thought to be in excess of $250 million. Adjusted for inflation, that amount today would be $3,287,083,318.

Last month, the final vestiges of W.A. Clark's estate were auctioned off. When his sole surviving heir, his daughter Huguette died in 2011 just weeks short of her 105th birthday, the portion of her father's fortune that had been left to her after his death when she was 19 years old was worth $300 million.

William Andrews "W.A." Clark is not of our time. He was born in a four-room log cabin in Connellsville, Pennsylvania on January 8, 1839. The United States was not quite 63-years old. It was a time of great change. The world was on the verge of the second industrial revolution, at which point America would take its place as a great world power for the first time. The year before W.A.'s birth, Samuel Morse sent the first long-distance telegraph. The year after his birth, the very first mechanical reaper for harvesting grain was sold. The number of stars on the flag of the United States of America had doubled from the original thirteen to 26. Arkansas and Michigan were the country's newest states. People were buying and reading some of the first books written by Americans. It was into this world that a very ambitious man was born.

W.A. had a knack for making money. After his schooling, Clark's first job was teaching in Iowa in 1857 and in Missouri in 1859-60. But this wasn't enough for the 20-year old's outsized ambition and energy. He enrolled at Iowa Wesleyan University for the princely sum of $25 tuition per year. He was simultaneously taking classes for his B.A. and attending law school. He'd be drawn away from his lawyerly ambitions after less than two years of studies by the gold rush.

Gold had been found in 1848 in California, setting off the great gold rush of 1849. By the time W.A. got wind of it (remember, news traveled extra slow in those days, which makes his story that much more remarkable), the focus was on Colorado. To get there, it took W.A. five months to travel by covered wagon from Missouri to present day Colorado Springs. It was a roughly 800 mile distance. After spending time working mines in Colorado for $3 per day. (roughly $69 today) and prospecting in Idaho, Montana, and Utah, W.A. came to the conclusion that this was not the way that he was going to get rich, no matter how ambitious he was.

W.A., soon found something that did net him a good return on his efforts and investment: sales and merchandising. W.A. would travel to Salt Lake City and Boise and bring flour, butter, eggs, "fresh" fruit, tobacco, and other sundries to the miners and prospectors staked out in remote areas of what was, at the time, still very much the wild, wild, west. Eggs that cost him 20 cents per dozen in Salt Lake City, he sold for $3 after completing the journey back to Montana. Tobacco bought at $1.50 a pound in Boise was told for $6 a pound in Helena, Montana.

But W.A. would move on from that venture. He found out he could make more money by taking the U.S. Mail from the Columbia River in western Montana up to Walla Walla, Washington. For this he made $22,400 per year (that's $386,401 today).

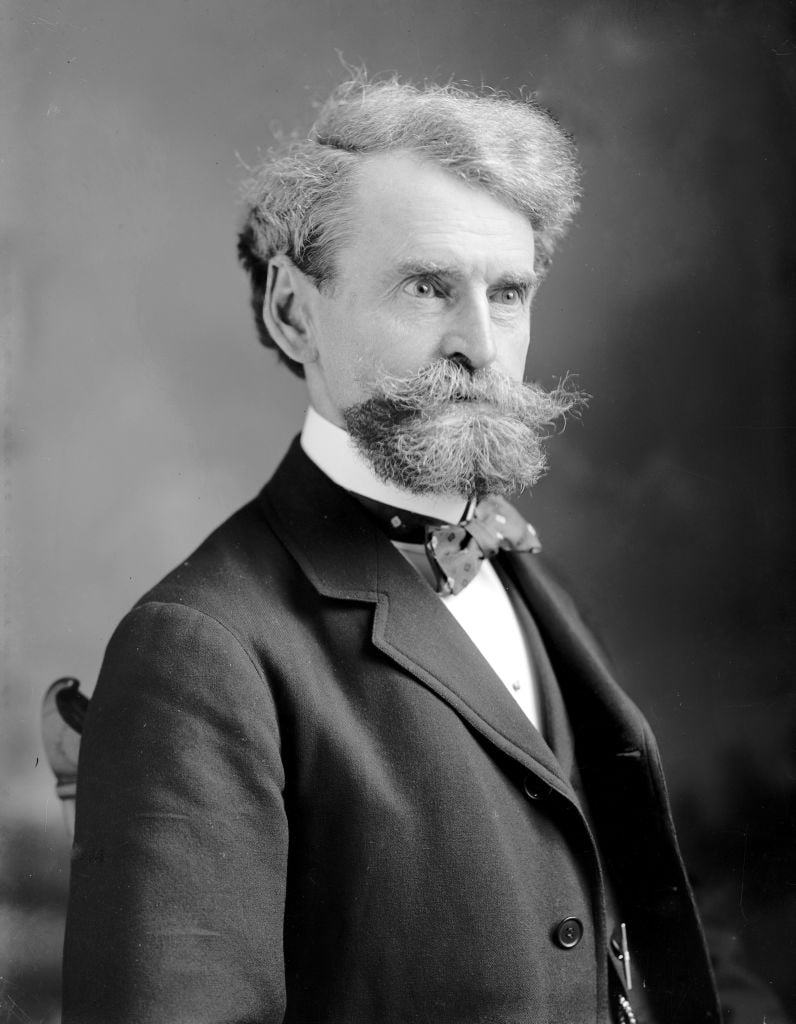

(Photo by: HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Clearly, W.A. had a knack for making money. He also had a pretty short attention span, moving from career to career nearly every other year. In 1872, after he had married his first wife, Katherine Louise Stauffer, W.A. found a new way to make a profit. He opened his own bank: W.A. Clark & Brothers. That same year, W.A. Clark bought four old mining claims of uncertain value. And he struck figurative gold in copper. Those mining claims, which he picked up for a very little, yielded 50% copper ore. Most successful and well producing mines yielded 5% ore. His United Verde mine in Arizona, picked up for nearly nothing, would prove to be the biggest producer of copper of them all. His shrewdness as a banker coupled with his newfound expertise at copper mining laid the foundation for the incredible fortune he built and would pass on to his daughter Huguette, born in 1906.

Of course, it was also all about being in the right time and place. The second industrial revolution changed the course of America and the inventions we now take for granted were dependent on Clark's copper.

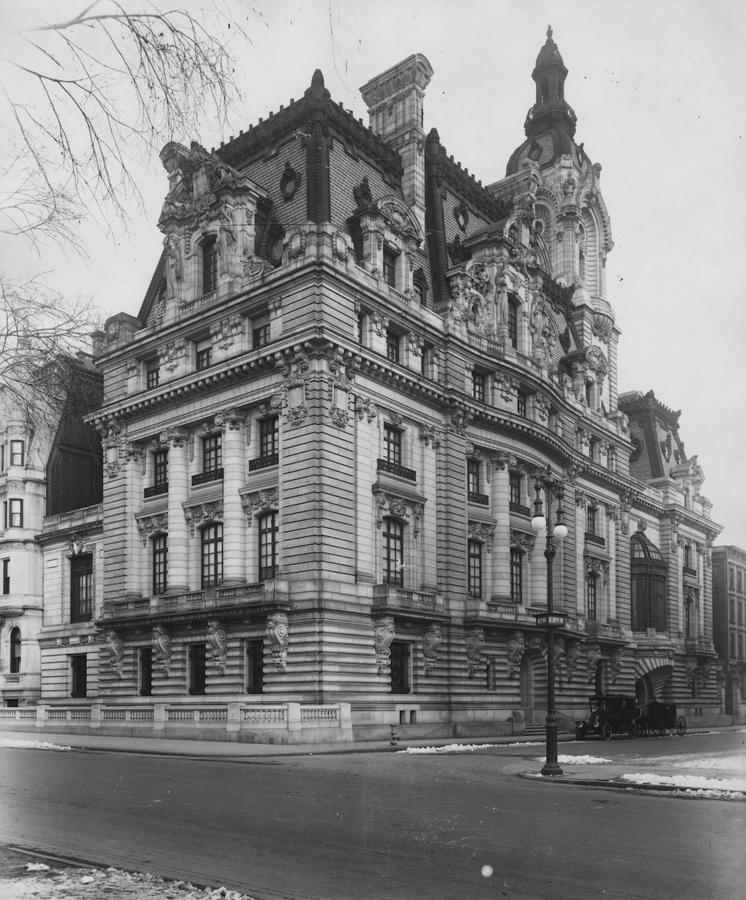

But W.A. wasn't satisfied with just great wealth. He also wanted social status and a title. He ran for Montana's U.S. Senate seat a number of times before successfully grabbing it (and later being forced out of office). His first wife died. He married his second wife Anna La Chappelle, who was 39-years younger than him. He built one of the great mansions of New York City's Fifth Avenue, on the same street as the Vanderbilts, Astors, and Carnegies. W.A. amassed a world class art collection full of Degas, Monet, Manet and other influential painters of his time period.

(Photo by Geo. P. Hall & Son/The New York Historical Society/Getty Images)

But most astoundingly, as W.A. Clark's wealth grew, his interests became spread out. He was managing businesses in New York, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Montana, Utah, and Southern California – all in the day and age before telephones, faxes, and emails; before air travel, before auto travel, even before widespread passenger train travel. In fact, when W.A. was faced with the problem of how to get supplies from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City with no railroad, he simply built his own.

Oh, and on that route, he also managed to auction off the land that would eventually become Las Vegas. Have you ever noticed that Las Vegas today is located in Clark County, Nevada? That's because of William A. Clark.

Was W.A. Clark a legitimate businessman who happened to get very, very lucky or a robber baron of sorts? The great American author Mark Twain said of Clark:

"He is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag. He is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a chain and ball on his legs."

It happens that, for all of W.A. Clark's ambition and exceptional skill at making money and identifying new money making ventures, he didn't foresee his own death.

While his contemporaries set up their businesses to operate though traditional hierarchies of Vice Presidents, Executives, Directors, and Managers, creating large and strong corporate empires that were built to last, W.A. ran his companies (and there were many of them) as sole proprietorships which he ruled absolutely autocratically.

W.A. quite adeptly handled every aspect of his companies himself – while he was alive. He failed completely in succession planning. In 1928, three years after his death, his heirs cashed out of the Clark mining interests in Montana. W.A.'s sons were expected to take over the companies, among them the mammoth United Verde copper mine in Arizona.

However, that was not to be. Charlie Clark, the eldest surviving son lived like the heir he was. He was a drinker, gambler, and womanizer who had been married three times. He died of pneumonia in April 1933 at the age of 61.

Will Clark Jr. had a law degree from the University of Virginia, and more closely resembled his father in intellect and ambition. He settled in Los Angeles, founded the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra and was a major donor in the construction of the iconic Hollywood Bowl. Will died in June 1934 at the age of 57 from a heart attack. He was rumored to be a binge drinker and homosexual who chased much, much, younger men. This was far more shocking in Los Angeles in the 1930s than it is today.

Will Clark Jr.'s only son, Will Clark III, was the family's best hope for carrying on W.A.'s legacy and running the family's holdings. In 1932, at age 29, W.A. Clark III died while taking flying lessons.

The male Clark heirs tendency towards self destruction left his daughters in charge and they had little interest in running the companies. In 1935, at the height of the Great Depression, when copper prices were at an all time low, May and Huguette Clark sold off the United Verde mine.

W.A. Clark's empire had been completely dissolved within a decade of his death.

However, his fortune survived for another nearly 80 years, mostly in the hands of his youngest daughter, Huguette. What happened to his wealth, his luxury homes, and his art collection, as well as the trajectory of Huguette's life—she lived to be nearly 105, dying in 2011 – is a mysterious and fascinating tale all on its own. She ended up living in a tiny, bland hospital room for two decades despite being worth hundreds of millions of dollars and having mansions all over the country.

/2018/02/gw.jpg)

/2021/03/Andrew-Carnegie.jpg)

/2013/09/GettyImages-468992138.jpg)

/2017/12/GettyImages-3318035.jpg)

/2014/12/thumb1.jpg)

/2021/07/GettyImages-3329759.jpg)

/2013/12/Evel-Knievel.jpg)

/2010/03/David-Faustino.jpg)

/2016/12/nunes2.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2020/10/Art-Garfunkel-1.jpg)

/2021/01/Paul-Simon.jpg)

/2020/01/Bruce-Buffer.jpg)

/2020/02/buffer.png)

/2020/08/billie-joe-armstrong.jpg)

/2014/09/Jarvis-Cocker.jpg)

/2009/11/Katherine-Heigl.jpg)

/2009/12/Bill-Maher.jpg)

/2012/06/Zach-Johnson.jpg)

/2020/11/barry-gibb.jpg)

/2010/03/Katey-Sagal.jpg)

/2013/07/Ben-Crenshaw.jpg)

/2010/04/vybz.png)