Whether you like Andy Warhol's work or not, there is no denying the incredible influence it had on the art that came after it, and pop culture in general. The eccentric, flamboyant painter, filmmaker, sculptor, and musician, churned out an incredible amount of work over a tragically short lifetime. Unlike many visual artists who spent their lives struggling to make ends meet, only to have their work fetch millions after their deaths, Warhol had a successful commercial art career that he left behind to focus on creating polarizing, ground-breaking, experimental art. He churned out an astonishing number of works. So many, in fact, that the Andy Warhol Museum in Pennsylvania is the largest museum dedicated to the artwork of a single artist in the United States. When he passed away in the late 80s, a bitter dispute began between those business associates who had been closest to him. At stake? An enormously valuable estate.

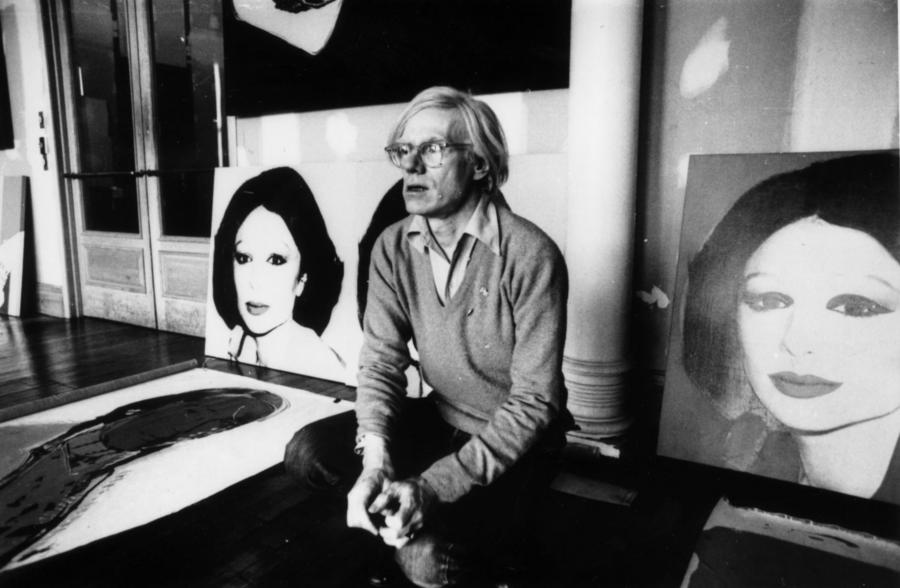

Graham Wood/Getty Images

Andy Warhol was born Andrej Vahrola, Jr. on August 6, 1928 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His parents emigrated to the United States from what is now known as Slovakia, and his father worked in a coal mine. He was sickly as a child. He developed the nervous system disease commonly known as St. Vitus' Dance, and spent much of his elementary school years confined to bed. It was during the years of illness that he began drawing and collecting pictures of movies stars. After graduating from high school, he originally intended to go to school for education. However, he ultimately chose to shift his focus, and began his college career at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where he majored in commercial art. He graduated with a B.F.A. in Pictorial Design, and relocated to New York to work in magazine illustration.

Warhol was an almost instant sensation within the design community in New York. He first rose to fame illustrating shoe advertisements. His whimsical ink drawings were a major hit, and became part of his first gallery show in New York. RCA Records caught wind of him, and invited him to design all of the record covers for their roster of artists. He also began experimenting with silk screening, and became known for leaving mistakes in his work. He didn't mind blotches, smears, or other imperfections, and it give his work an immediacy that was uncommon at the time.

The 1960s saw him challenging what pop art could be. He began producing paintings, silk screens, and illustrations of iconic American products and people, such as Campbell's Soup, Coca Cola, Elvis Presley, and even particular headlines in the newspaper. His images challenged the art world's idea of what constituted art, and became popular with wider audiences. At the same time, he began to actively attract other cutting edge artists, filmmakers, performers, and patrons. He turned his studio space into what became known as "The Factory". A bohemian enclave that was part workspace, part hang out, "The Factory" was both where Warhol produced his paintings (with an army of assistants), and where he shot films, hosted parties, and held the occasional rally. In establishing "The Factory", he built a free-wheeling underground art scene in New York that was initially quite successful.

However, it all came crashing down in 1968, when a radical feminist and actress named Valerie Solanas, shot him in his studio. She'd previously appeared in one of Warhol's movies, and had given him a script to read. He misplaced it, and when she came to pick it up, he couldn't find it. She left, came back later in the day, and shot Warhol and a visiting friend, art critic and curator, Mario Amaya. Doctors were forced to reach into his chest and to massage his heart in order to keep him alive. The shooting left him permanently damaged, and he was forced to wear a surgical corset for the rest of his life. After that, "The Factory" became noticeably less all-inclusive, and the party animal portion of Warhol's personality largely disappeared. He became much more business oriented, and focused on landing big money patrons and major commissions. He also launched his own magazine called, "Interview", and founded the New York Academy of Art in 1979. By the 80s, his style of work had fallen out of favor. He was largely focused on portraiture, creating images of political figures, celebrities, and other people in the public eye. Though his own work wasn't winning raves, he became known as a mentor of sorts for a number of up-and-coming artist including Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Francesco Clemente.

He passed away on February 22, 1987 due to complications after a routine gallbladder surgery. He had collected so many things over the course of his 58 years, that it took Sotheby's nine days to go through and catalog his possessions. His personal effects were valued at $20 million. In his will, he stipulated that a few personal items were to go to his family, but the rest of his estate was meant to fund the creation of a foundation for the "advancement of the visual arts". That's where things went pear-shaped. Warhol was an incredibly prolific artist, and had written books, run a magazine, written, designed, directed, and/or produced 60 full-length projects, and nearly 500 short, experimental works. He'd also painted hundreds of works, sometimes alone, sometimes with collaborators. Some of his works had been reproduced by his team of resident artists. He'd also produced photographic works, computer-generated digital art, written and produced plays, designed clothes, and produced a number of sculptures. At one point, he even carried around a portable tape recorded and recorded every conversation he had. He had 4,118 paintings, 5,103 drawings, 19,086 prints and 66,512 photographs to be exact, some of which were truly legendary pieces of art. The end result was that his artwork was worth quite a lot more than the rest of his household items. For the next six years, three men fought over his artistic legacy, and the art world watched with barely disguised glee.

When Warhol passed away, Frederick W. Hughes, was his business partner and the first head of the Warhol Foundation. Mr. Hughes became seriously ill after Warhol's death, and Archibald Gillies became the head of the Warhol Foundation in 1990, three years after it was established. Unfortunately, Mr. Hughes and Mr. Gillies did not get along with regards to how to run the Foundation. Adding to the tension was Edward W. Hayes, the lawyer in charge of the Warhol estate. Mr. Hayes was entitled to 2% of the value of the estate per contract. Mr. Hughes had fired him, and Mr. Hayes wanted to be paid what he believed he was owed. He valued Warhol's estate at somewhere between $400 and $600 million. When Christie's finally determined the value in 1993, it proved to be a healthy, but far lower, $220 million. Warhol works were no longer all the rage, and with less demand, came lowered prices.

With the settlement, Frederick Hughes was paid $5.2 million for his part in helping to establish and run the Warhol Foundation. The Foundation was then earmarked to receive the rest. The biggest loser was Mr. Hayes. He'd already been paid $4.85 million for his work as Warhol's lawyer after his death. Unfortunately, this meant he actually owed the Foundation almost half a million dollars. Ooops. Since then, the majority of the Foundation's money has been poured in to building and launching the Andy Warhol Museum, as well as funding rising artists. It's strange to think that, even after his death, Andy Warhol's work still proved to be a great source of controversy.

/2014/07/Andy-Warhol-1.jpg)

/2016/11/Andy-Warhol.jpg)

/2015/07/one.jpg)

/2017/07/GettyImages-484046316.jpg)

/2022/03/jackson-pollack.jpg)

/2014/04/david-hockney.jpg)

/2021/10/John-Boyega.jpg)

/2010/11/josh.jpg)

/2022/05/Nayib-Bukele.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2010/11/russell-armstrong.png)

/2013/07/courtney-henggeler.jpg)

/2021/12/Lauren-Sanchez.jpg)

/2020/10/cate.jpg)

/2018/04/GettyImages-942450576.jpg)

/2021/08/bert-kreisher.jpg)

/2021/09/tom-segura.jpg)

/2023/09/john-mars.png)

/2010/01/Orlando-Bloom.jpg)

/2020/10/neil-young.jpg)

/2010/06/dario.jpg)

/2014/01/GettyImages-539540466.jpg)

/2012/08/broner.jpg)