Before the money started flowing in, before the fancy cars and the big shipments, before the Feds were on to him, drug kingpin Ricky Donnell Ross (more commonly known today as "Freeway Ricky Ross"), wanted to be a professional tennis player. And it looked like he had a shot. Ricky was the star of his high school tennis team in South Central LA and seemed bound for a college scholarship. Unfortunately, those scholarship offers disappeared when his coach realized Ricky was totally illiterate. Ross, who at the time was living in a one-car garage with up to fifteen people at a time, was forced to turn to what seemed like the next most-plausible path to success: Dealing drugs. At first, Ross's drug deal ambitions were short-term and small-scale. Ross would recall years later:

"At the time we were doing $50 packages of powder cocaine, and making maybe $25. That garage was all I wanted, I thought I would live there forever. Maybe fix it up, get a nicer bed."

Ross claims that at first, he had no intentions of dealing for a long time; get in, make money, get out. As he was about to learn, in the extremely lucrative world of drug dealing, that can be easier said than done.

Ricky's life took a big turn when he was introduced to Oscar Danilo Blandón, a Nicaraguan ex-pat who had fled to the United States in 1979 when the Somoza government, to whom his family was connected, was overthrown. Blandón offered Ross an incredible deal on cocaine. Blandón allegedly had a connection to the legendary Nicaraguan cartel boss Norwin Meneses and could offer the budding entrepreneur an absoluely amazing price on wholesale quantities of cocaine.

"Where other people were getting $3000 an ounce, I was getting $1800. There was no limit to what we could do."

By the time he was twenty years old, Ross was living the life of a full-blown ghetto superstar. He bought a party house for $250,000 in single dollar bills. He established more than a dozen cookhouses around Los Angeles. He took up the name Freeway Ricky Ross, on account of real estate he owned near the freeway. He was Supafly come to life. The Rolls Royce, the mink coats, the pimp cane. All before he was even old enough to drink a beer!

With Blandón's help, Ross moved up to $3 million dollars worth of cocaine per day. Between 1982 and 1989, Ross bought and sold over several metric tons of cocaine. DEA agents and Federal prosecutors would later testify that during his nearly 10 year run, Freeway Ricky Ross grossed $900 million. These same agents and lawyers claim that Ross personally profited a minimum of $300 million. After inflation adjusting, Ross grossed the equivalent of $2.5 billion dollars and personally profited $850 million dollars.

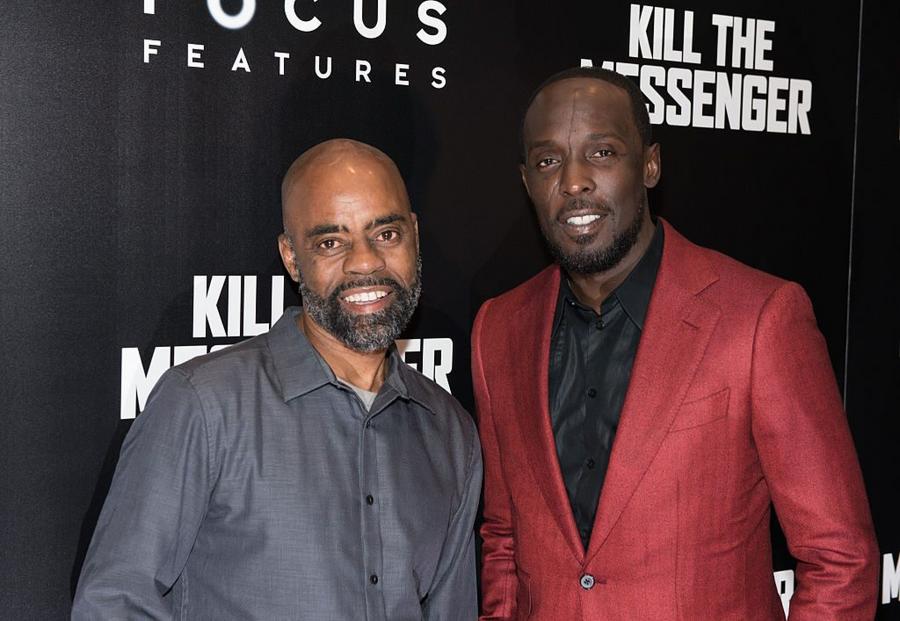

Freeway Ricky Ross / Dave Kotinsky/Getty Images

In Blandón, Ross found more than just a connect. The Nicaraguan became a mentor to Ross, a father figure, someone who he could trust. "I looked up to him," says Ross. "I tried to copy his moves, how he handled his business. We got to the point where every time we bought from him we wanted more drugs – we wanted to show him that we were investing in the business." Ross was so loyal to Blandón that he missed some of the red flags, clues that there was more to his hero than Ross realized.

Blandón provided Ross and his crew with extravagant guns, including a grenade launcher. He had specialized scanners to monitor the DEA, and on more than one occasion, he tipped Ross off to imminent raids. All of these things should have raised some eyebrows, but as Ross points out, "You don't ask the goose, 'why you laying golden eggs?' You just take the eggs!"

The biggest hint that Blandón might have something else up his sleeve came in 1992 when he was arrested. Even though he had been moving as much as 100 kilos of cocaine per day, Blandón only served a two-year sentence. And then, unbeknownst to Ross, he became an informant for the DEA. And that could only mean one thing was in store for Freeway Ricky Ross.

The trap was set in San Diego in 1986. As Ross recalls: "Blandón called, saying he got 700 kilos to get rid of. And I didn't want to do it. I wanted out. But I wasn't making any money and all he was asking for was a connection. So I said 'Chico Brown'. I was with Chico at this restaurant up on Hoover at the time. I told him I didn't want to be at the deal, I didn't want to be around the drugs, I just wanted to make the connection and leave."

If not blinded by his trust for Blandón, Ross might have smelled a trap: Blandón usually made his deals at night, but insisted that this one take place during the day and he demanded that Ross come to San Diego instead of Los Angeles. He also demanded the money upfront – something he had never done before.

"It was my destiny, I guess," Ross says. "I had to go." And they got him. Slapped a life sentence on him, too. It wasn't until later that Ross realized that Blandón, who had been sending money to the Contras, might have also been supported by the CIA all along. The theory has never been proven, but journalist Gary Webb lent credit to the theory in his book "Dark Alliance".

Behind bars, Ross read personal development books and Bill Gates' biography, absorbing any advice for entrepreneurs. He got up at 5 AM every morning and did his pushups. He was a model prisoner. Against the odds, his sentence was eventually reduced to 20 years. In 2009, he walked out a free man.

Will Ross ever be able to regain his past wealth? Likely not, if he's going to play it straight. But that doesn't mean his hustle is over. Now he's working on a million different projects: giving motivational talks, working on a film about his life directed by Nick Cassavetes (Blow, John Q.) and he is about to release his autobiography, written with the help of veteran hip-hop writer Cathy Scott. Ricky Ross may be done selling drugs, but he's still hooked on hustling.

/2016/11/cocaine.jpg)

/2012/09/ricky2.jpg)

/2016/06/GettyImages-691358450.jpg)

/2011/07/frank.jpg)

/2015/11/GettyImages-1611508.jpg)

/2011/01/meech.jpg)

/2021/10/John-Boyega.jpg)

/2010/11/josh.jpg)

/2022/05/Nayib-Bukele.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2010/11/russell-armstrong.png)

/2013/07/courtney-henggeler.jpg)

/2021/12/Lauren-Sanchez.jpg)

/2020/10/cate.jpg)

/2018/04/GettyImages-942450576.jpg)

/2021/08/bert-kreisher.jpg)

/2021/09/tom-segura.jpg)

/2023/09/john-mars.png)

/2010/01/Orlando-Bloom.jpg)

/2020/10/neil-young.jpg)

/2010/06/dario.jpg)

/2014/01/GettyImages-539540466.jpg)

/2012/08/broner.jpg)