Bruce P. McNall made a fortune in the 1970s by selling pristine antique coins to collectors. He parlayed that wealth and status into sports, becoming owner of both the NHL's Los Angeles Kings and the CFL's Toronto Argonauts, and winning the most prestigious thoroughbred horse race in France. He also produced several Hollywood movies, including Weekend at Bernie's and The Manhattan Project. And for good measure, he owned multiple homes and a Boeing 727.

Then, in a flash, it all disappeared. Suddenly, McNall had nothing, a position he hadn't ever found himself in before. So what exactly happened? How did a guy who had big celebrities like Tom Hanks, Kurt Russell and Goldie Hawn on speed dial lose everything? And perhaps more impressively, how did he remain in Hollywood's good graces?

Really, it's thanks to his terrific networking ability. The man is a schmoozing machine. McNall built up his riches through his charm, and helped boost his work via bankers and brokers. He used the Kings as a way to borrow millions of dollars, and as chairman of the league's board of governors (the second highest position in the NFL), he persuaded both the Walt Disney Company and Wayne Huizenga, the founder of Blockbuster, to purchase NHL teams as well.

McNall was pairing the celebrities he knew with bankers' money. It seemed like a win-win; the bankers got to rub elbows with A-listers, while the stars received money to pursue their interests. The main problem: McNall's businesses stopped making money in the 1990s, and in 1994, he was forced into liquidation for defaulting on $160 million in loans.

McNall, who was born on April 17, 1950 in Arcadia, California, developed an interest in trading ancient coins as a child. He studied Roman history at UCLA, and by his mid-20s, he had a coin shop on Rodeo Drive. Soon, he was traveling the world in search of coins with Texas financier Nelson Bunker Hunt. It was Hunt who introduced McNall to the silver, sports and horse worlds.

Even though he was only 24, McNall adhered to the adage "spend money to make money." In 1974, he paid $420,000 – a sum that was four times more than the previous record – for the Athena decadrachm, from the fifth century B.C. It's the rarest coin in the world. He purchased the Kings for $15 million, and then agreed to pay Wayne Gretzky that much over 10 years to bring him over from the Edmonton Oilers.

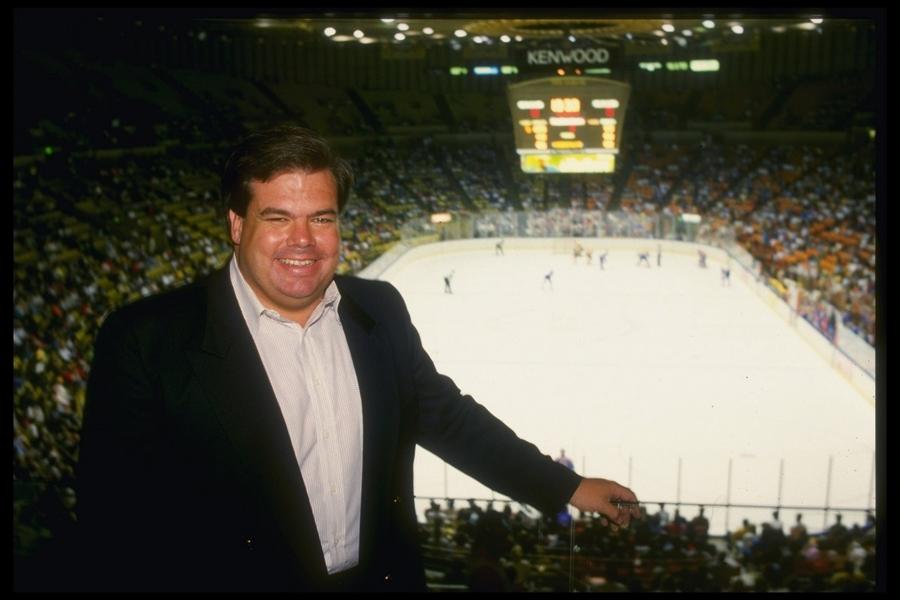

Getty Images

Making fast friends with Gretzky, McNall went in with The Great One on the Argonauts in 1991. Along with actor John Candy, the trio purchased the team for $5 million and immediately signed Rocket Ismail, an electrifying wide receiver and return man out of Notre Dame, to a four-year, $18.2 million contract. The move was notable for a pair of reasons: that was a ton of money to give a player in that era, and prior to signing with the Argonauts, Ismail was playing in the NFL. The fact he bolted from the more established league is further testament to McNall's suave business savvy.

As L.A.'s hockey team, Kings' home games naturally featured a lot of celebrity sightings. Perhaps fueled by fans wanting to catch a glimpse of the Hollywood lifestyle, ticket and merchandise sales skyrocketed. Sensing the benefit of a Southern California rivalry, McNall convinced Michael D. Eisner, Disney's chairman, to start an expansion team in Anaheim in 1993. McNall got a $25 million kickback from Disney for accepting a team in his home territory.

But for all that spending, McNall's Kings teams never made money while he owned them. The biggest reason for this was that the team had to fork over a lot of cash to play its home games in the Great Western Forum, owned by then-Lakers owner Jerry Buss. Anyone who's been to a Lakers game knows they do extravagance to the max.

Meanwhile, McNall's coin-collecting business was boosted by creating artificially high values for the ancient coins he was peddling. He did this by introducing his investors to a market dominated by collectors. The market fell in the late 80s, so McNall turned to the banks, in particular Merrill Lynch, and raised almost $49 million in limited partnerships. Again, though, McNall wasn't able to obtain the profits he thought he could, and the first two funds were liquidated. But even though those funds lost money, McNall still made some for himself, as companies paid him to manage and collect coins.

Gary Newkirk/ALLSPORT

As it turned out, the coin company was also about to run into trouble. In December 1993, Bank of America told McNall that he had defaulted on a $90 million loan collateralized by the Kings; if he didn't sell the team by the end of the month, Bank of America would force bankruptcy upon them.

McNall finally found a company to sell to: telecommunications company IDB Communications Group, which had just merged with LDDS Communications. Bank of America ultimately financed $50 million of the $60 million purchase price for a 72 percent stake.

Though McNall had to give up controlling ownership of the team, he was still able to hang onto the other 28% of his stake and remained president and governor for a time afterwards. Court documents show that the bank took the $60 million in proceeds and a different $12.5 million from Disney, half its payment for expanding into Anaheim with the Mighty Ducks. Bank of America also grabbed a 10 percent stake in LDDS Communications. And, in slightly good news for McNall, the bank released him from its remaining $30 million claim, so he could use that collateral to pay other creditors.

But that was the lone bright spot for McNall. His movie company, Gladden Entertainment, was forced into bankruptcy. Just two weeks after the Kings were sold, McNall had three separate banks that filed for Chapter 11.

Mr. McNall's empire was fast coming unglued. The Federal grand jury had subpoenaed his business records and those of his associates. His movie company, Gladden Entertainment, creator of "Mr. Mom" and "The Fabulous Baker Boys," was forced into bankruptcy in April by debt. About two weeks after the Kings were sold, three of Mr. McNall's banks, Credit Lyonnais, IBJ Schroder and European American Bank, filed a petition for involuntary bankruptcy, a case that has since been converted into a Chapter 11 reorganization.

McNall's downfall caused problems for Merrill Lynch, as well. Numismatic, McNall's coin company, resigned as general partner, and while sorting through the inventory, Merrill Lynch found that 399 coins (a $3.3 million value) were missing from the World Coin Fund. That led to one lawsuit from investors; a second suit followed, this one accusing Merrill Lynch and McNall of acquiring coins in the funds illegally. McNall confirmed those accusations in an interview where he said he smuggled coins from foreign countries and that the bulk of coins in two Merrill Lynch funds were taken illegally. The coins were eventually reclaimed by their rightful owner, who McNall had been paying $100,000 a month. He probably got at least some of that money from charging a Merrill Lynch fund $4 million for his purchase of those coins, then wired the money to a Swiss company he owned. Very sneaky!

On December 14, 1994, Bruce McNall pleaded guilty to five counts of conspiracy and fraud, and admitted to bilking six banks out of $236 million during a 10-year period. He was sentenced to 70 months in prison, though he got out 13 months early on good behavior. His fraudulent spending trickled down to the Kings, too, as the team filed for bankruptcy in 1995 and remained in dire financial straits for several years after.

While in prison, McNall was visited by friends like Gretzky, Kurt Russell and Goldie Hawn, and received letters and well-wishes from the likes of Eisner, Tom Hanks and television producer Barry Kemp. In 2003, McNall wrote a book called Fun While It Lasted: My Rise and Fall in the Land of Fame and Fortune, and still continues working in the movie industry, albeit in a much smaller production role. Today, he has a modest net worth of $3 million, and runs ProCon.org, a charity that, according to the website, is "dedicated to promoting critical thinking, education, and informed citizenship by presenting controversial issues in a straightforward, nonpartisan, primarily pro-con format."

Hopefully, McNall is a little more even-keeled this time around, but one thing's for certain: If he gets into trouble, he'll have plenty of friends he can call on for support.

/2009/12/wayne-gretzky.jpg)

/2016/02/GettyImages-457609018.jpg)

/2015/03/GettyImages-466413070.jpg)

/2014/09/Waddesdon-Manor.jpg)

/2020/04/kurt-russell.png)

/2018/07/GettyImages-1717128-e1531370968811.jpg)

/2013/12/dan.jpg)

/2011/12/John-Mara-1.jpg)

/2020/08/gc-1.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2011/12/Rooney-Mara1.jpg)

/2014/04/GettyImages-886617106.jpg)

/2020/03/favre.jpg)

/2010/12/kate-1.jpg)

/2022/10/peter-krause.jpg)

/2020/10/the-miz.png)

/2011/01/Aaron-Rodgers.jpg)

/2014/08/sp-1.jpg)

/2020/07/jared-kushner.jpg)

/2013/10/Bernadette-Peters-1.jpg)

/2010/03/emil.jpg)

/2016/01/Kirk-Cousins.jpg)

/2024/10/Jordan-Love-.jpg)