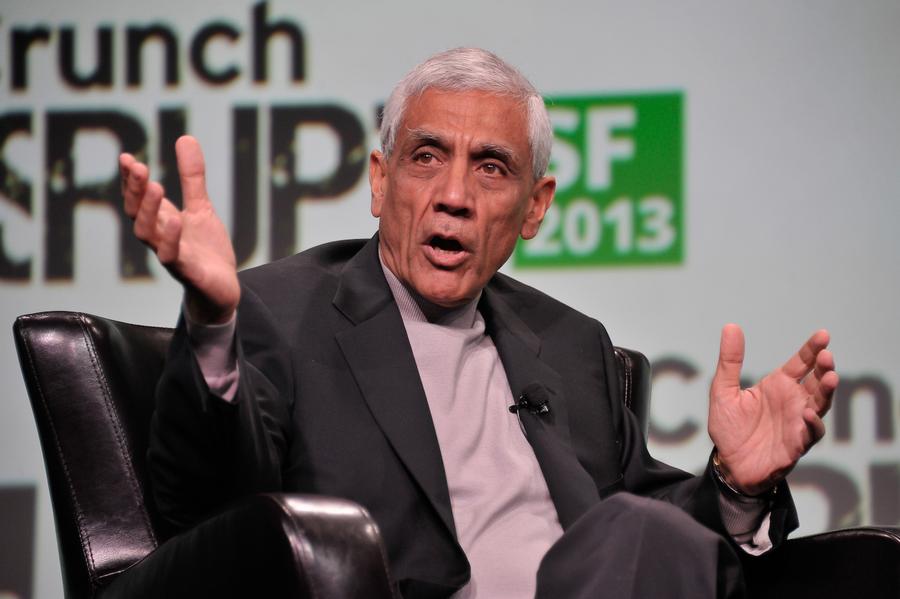

It seems like tech billionaire Vinod Khosla has been battling over Martin's Beach for eons. The Sun Microsystems co-founder has wanted the formerly beloved public beach with access only via a private road that goes through his estate to be his, and his alone. He has been battling California environmental advocates and regulators for years. He's lost each and every legal battle. Now Khosla is trying to take his case to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that California's interpretation of the law and insistence that people be allowed to cross his property en route to Martin's Beach "crosses a constitutional line."

Access to the beach has been under dispute since Khosla bought 53 acres of land adjacent to Martin's Beach in 2008. The previous owners had allowed public access to the beach for nearly 100 years. Khosla began locking the gate to the private access road in 2010, setting this long legal battle in motion. This move to the Supreme Court could set in motion an enormous change for how California views public lands.

For decades, the California Coastal Act has declared that access to California's beaches is a fundamental right guaranteed to everyone. The commission sets regulations for all of California's coastline including managing coastal development and protecting wetlands.

Steve Jennings/Getty Images

The California Coastal Act for decades has scaled back mega-hotels, protected wetlands and, above all, declared that access to the beach was a fundamental right guaranteed to everyone. The Supreme Court could decide to dismantle all of that. And to think, this case began as a local dispute in Northern California over a locked gate.

The legal battle breaks down like this: Vinod Khosla wants a secluded bit of beach in San Mateo county called Martin's Beach all to himself. On the other side, beachgoers, fishermen, and picnickers who have been enjoying Martin's Beach for decades, want to keep doing so. Khosla has locked the gate, blocking the only access to Martin's Beach. His opponents want continued access to a beach that has been available to the public for about 100 years. The Denney family had previously owned the Martin's Beach land. They maintained a public bathroom, parking lot, and general store. Surfers, sun worshippers, fishermen, and picnickers paid 25 cents for beach access. Over time, that fee went up to $10.

Khosla admitted in legal filings that he tried to keep that same practice in place, but the business was operating at a considerable loss. So, he shut the gate, posted do not enter signs, and hired security guards.

The battle kicked off all the lawsuits. Khosla wanted the legal right to gate off the road and keep the public out. Each and every lawsuit has denied the billionaire that right. You'd think he'd back down. But no, he is a billionaire with unlimited resources to throw at this battle. So, Khosla is now attempting to take his case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

His case challenges whether or not the California Coastal Act violates his constitutional rights and it also throws a light on whether or not California actually has the right to restrict coastal development and allow beach access to all. It is a bold and arrogant move that is trying to drive a stake through the center of California's society. This case could set off a string of lawsuits that will threaten not just California, but every coastline in the United States.

In order to make his Supreme Court case more legit, Khosla has hired an attorney with the credentials to get his longshot case heard by the Supreme Court. Paul Clement served as solicitor general under President George W. Bush, clerked for the late Supreme Court judge Antonin Scalia, and has argued more cases before the Supreme Court in the past 18 years than any other attorney in the world. Clement is known for defending conservative positions. He has argued against same sex marriage and he led the challenge to the Affordable Care Act. Clement's 151 page petition to the Supreme Court calls California's coastal laws "Orwellian." He is attempting to make the case that private property should not be mandated as pubic without compensation to the land owner.

It will take about three months for the Supreme Court to decide whether they will hear Khosla's case. His chances are not good. Thousands of appeals are filed every year and only roughly 100 are heard by the Supreme Court. The President's appointment of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court slants the bend towards the conservative side. A well thought out and written argument might be enough to get the four Supreme Court votes needed for the case to move forward.

The long journey to a potential Supreme Court decision began when the Surfrider Foundation sued Khosla for failing to apply for the development permit needed to change the status of public access to the coastline. A local court agreed with Surfrider. A state appeals court upheld the decision and ordered Khosla to unlock the old gate. Khosla tried to take the case to the California Supreme Court, but they refused to hear the case.

Khosla is not the first billionaire to challenge California's coastal regulations. David Geffen was embroiled in a 22-year fight with the state to unlock the gate to the beach near his Malibu gate. He lost that battle. Conversely, James and Marilyn Nollan were ordered by the California Coastal Commission to allow the public to walk on their beach in Ventura in the 1980s. In exchange, they would be granted a building permit to enlarge their house. In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that the Coastal Commission had gone too far.

The difference between the Nollan case and Khosla's is that the Nollans followed the required steps of trying to obtain a permit before they restricted access to their beach. Khosla skipped that step and took his battle directly to the courtroom. He is arguing that the state's requirement that he obtain a permit violates his rights as a property owner. It is a direct attack on the state government.

Only time will tell if Khosla will get his date with the Supreme Court.

/2020/01/GettyImages-885066838.jpg)

/2016/05/GettyImages-180366422.jpg)

/2017/08/GettyImages-455060868.jpg)

/2017/06/GettyImages-455060868.jpg)

/2019/03/GettyImages-959404614.jpg)

/2021/10/John-Boyega.jpg)

/2010/11/josh.jpg)

/2022/05/Nayib-Bukele.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2010/11/russell-armstrong.png)

/2013/07/courtney-henggeler.jpg)

/2021/12/Lauren-Sanchez.jpg)

/2020/10/cate.jpg)

/2018/04/GettyImages-942450576.jpg)

/2021/08/bert-kreisher.jpg)

/2021/09/tom-segura.jpg)

/2023/09/john-mars.png)

/2010/01/Orlando-Bloom.jpg)

/2020/10/neil-young.jpg)

/2010/06/dario.jpg)

/2014/01/GettyImages-539540466.jpg)

/2012/08/broner.jpg)