The Vanderbilt family is one of America's oldest "old money" families. They rose to great wealth during the Gilded Age in the latter part of the 19th century. It all started with Cornelius Vanderbilt, whom many consider to have been the greatest capitalist in history. In 1810, then 16-year-old Cornelius borrowed $100 from his mom. From that original $100, he built a fortune of around $100 million. Adjusting Cornelius Vanderbilt's fortune for inflation, that would be equal to about $200 billion today. That kind of wealth was unheard of back in the 19th century. That's the kind of wealth that lasts for many generations. However, that wasn't the case with the Vanderbilt fortune. Within 50 years of Cornelius' death in 1877, his fortune was completely gone.

Cornelius was a shipping magnate. He started his shipping business with one boat and eventually built it into a small passenger fleet. He then moved into the steamboat business. By the time he was 50, he had amassed a fortune and turned to building a railroad empire. He stayed focused on his railroad business until his death at 82.

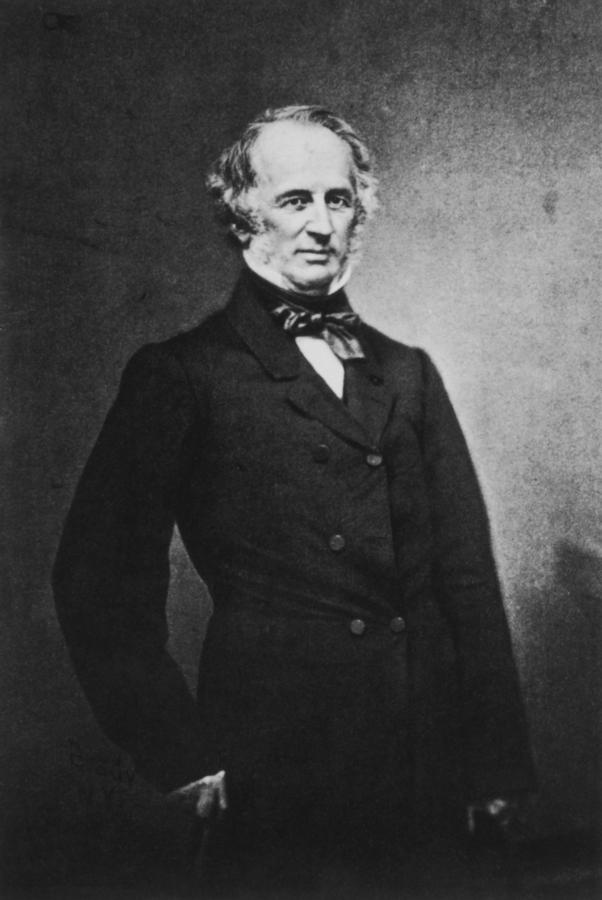

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

He was successful at every turn largely because he had a natural talent for business. He knew how to gauge his competition, handle the money, control the costs, keep an eye on the revenue, manage the deals, and network. He believed in free competition, letting things take their own course, and he wanted to keep the government out of free enterprise.

For instance, when Cornelius got into the shipping industry, it was run by companies that controlled monopoly rights on certain lucrative routes. Cornelius got around this by cutting costs, building faster ships, and cutting fares to nearly nothing. This practice drove many of his competitors out of business. When he moved into the railroad business, he kept up the same practices.

When Cornelius died, his son William took over the family businesses and fortune. William had his father's talent for business and doubled the Vanderbilt fortune to $200 million before his death in 1885.

circa 1925:Fox Photos/Getty Images

And then things began to decline. William's family inherited the vast fortune and had no desire to work to increase it or even maintain it. They lived extravagant lifestyles. They built enormous estates in expensive locals frequented by the rich and famous. Ten of those homes were palatial mansions in Manhattan. The Vanderbilt heirs were driven by ego and entitlement, squandering money left, right, and center.

Just 30 years after Cornelius' death, not a single member of the Vanderbilt family was among the richest in the U.S. Within 50 years, the fortune was completely gone.

There is a lesson in this. Sure, Cornelius' heirs spent money like it was going out of style, but the family fortune should have been merely lessened, not decimated.

Where Cornelius (and later William) went wrong is in not diversifying his wealth. All of his money was in shipping and railroad stocks. That worked for Cornelius, because he was very involved in the day-to-day running and managing of his companies. That wasn't the case with his heirs. When the family fortune is tied up in shares of companies the family owns, it is too easy for someone to say, "let's sell some shares," to fund whatever vanity project has caught their attention.

The second big issue with the Vanderbilt fortune is that it had hardly any true assets. It did not have any land or real estate assets. Cornelius owned no investment properties. Despite his vast wealth, he failed to buy real estate in Manhattan, even though he was running his businesses from there. Cornelius was focused on dividends and blind to the cash flow that could come from being an investor in the New York City real estate market. If the Vanderbilt fortune had even just 25% of it invested in land and buildings that would have been harder for his heirs to sell on a whim. That may have preserved the family fortune for future generations.

/2015/05/thumb7.jpg)

/2014/01/corn.jpg)

/2015/08/GettyImages-90093858.jpg)

/2014/11/GettyImages-106544513.jpg)

/2015/05/thumb6.jpg)

/2014/09/John-D.-Rockefeller.jpg)

/2010/11/josh.jpg)

/2023/10/elaine-wynn.jpg)

/2021/10/John-Boyega.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2020/10/cate.jpg)

/2010/11/russell-armstrong.png)

/2021/04/William-Levy-1.jpg)

/2014/05/Daisy-Ridley.jpg)

/2020/03/steve-wynn.jpg)

/2018/04/GettyImages-942450576.jpg)

/2013/07/courtney-henggeler.jpg)

/2022/05/Nayib-Bukele.jpg)

/2010/03/nc.jpg)

/2021/11/rich-vos.jpg)

/2012/08/broner.jpg)

/2014/06/oscar.jpg)

/2010/05/Lenny-Kravitz-1.jpg)