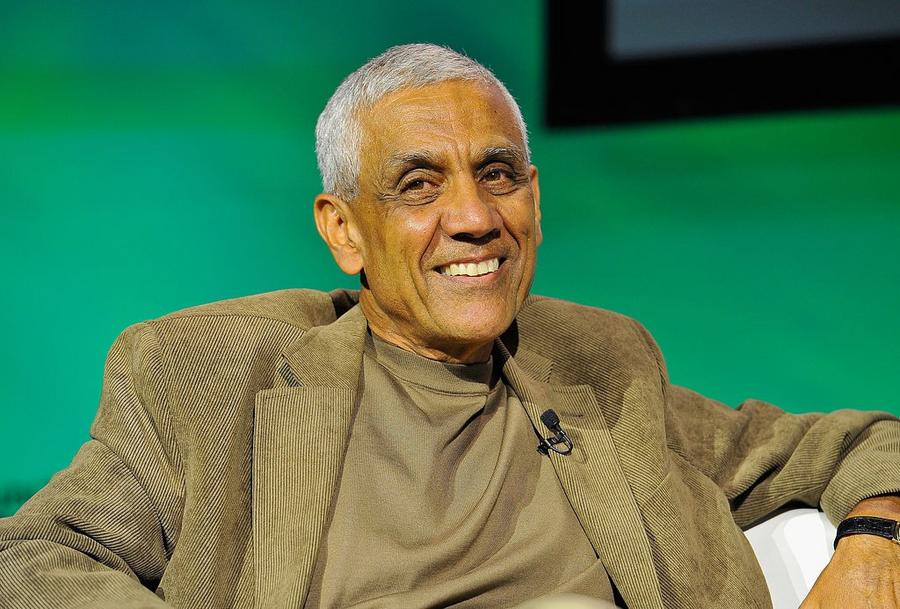

Vinod Khosla made his fortune by co-founding Sun Microsystems. He became a tech industry legend as a partner in the venerable venture capital firm, Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, and Byers. Over the past decade, the Indian-American billionaire has turned his attention to green energy through his startup, KiOR. He's made an ambitious push for clean energy, but lawsuits accusing fraudulent behavior mounted against the company and drove his startup into bankruptcy. Now, his bet on biofuel is looking like a losing battle, as well. Khosla is not used to being in such a position. With a net worth of more than $1 billion, he has never faced failure on such a grand scale in his long and storied career. What is it that happened with KiOR and the dream of clean energy Khosla holds so dear?

A few hours outside of Jackson, Mississippi lies the small town of Columbus. In the town is a factory that was once at the cutting edge of the biofuel revolution. It was able to turn wood chips into fuel that could power vehicles. This fuel would be cleaner than oil and better for the environment. It was a brand new technology that amazed everyone, from investors, to engineers, to politicians.

The people of Columbus, Mississippi once saw the factory as a way to provide hundreds of jobs to a region that remains chronically economically depressed. After all, the factory was owned by a publicly traded company worth more than $1.5 billion – so what could go wrong? The Columbus facility was the first of several to be built in Mississippi. It was supposed to reinvigorate the state's timber industry.

Today, just three and a half years after the facility opened to great fanfare (and even greater hope), it lies dormant. It hasn't produced any of its revolutionary biofuel in two years. The plant had been a former paper mill and cost more than $215 million to buy and convert for biofuel production. It was sold in 2014 for $3.7 million.

Steve Jennings/Getty Images

The factory was once a symbol of the promise of biofuels. It was also a symbol of the gravitas of Silicon Valley money and government influence.

KiOR was once the most important piece of Khosla's portfolio. Khosla is largely considered to be the most successful venture capitalist of all the time. He left the legendary venture capital firm Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, & Byers in 2004, to launch Khosla Ventures because he wanted to invest his time, energy, and money on developing sustainable clean energy. Over the past decade, Khosla has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in a dozen biofuel and biochemical companies.

Khosla Ventures held 75% of KiOR's voting shares and bet $160 million on it – most of it Khosla's own money. Former Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice joined KiOR's board, and Bill Gates invested in the company. Former Prime Minister of the U.K. Tony Blair joined KiOR as a Senior Advisor. There was so much promise for KiOR, and yet, just a few years after a gala groundbreaking, the Mississippi facility stopped production.

The technology behind KiOR's biofuel was born in Holland. Dutch chemical engineer Paul O'Connor launched a startup called BIOeCON in 2005. His plan was to use a process similar to the one used by the oil industry, but to make biofuels. The technology is called catalytic cracking. It uses a catalyst to break down biomass, such as wood chips. Even a decade ago, many companies were searching for a way to produce fuels using plant waste, rather than corn or other sources that can put stress on food supplies.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

At the same time, Silicon Valley's venture capitalists were looking for the next big thing. They'd made billions funding technology startups and they were trying to predict the next big industry. In 2006, when O'Connor began seeking funding, Silicon Valley's wallets were wide open. Khosla Ventures was one of the most aggressive companies in its focus on clean fuels and seemed a natural fit. O'Connor and Khosla partnered up. They intended to create a biofuel giant that could rival the big oil companies.

KiOR made a number of critical missteps from the start. Khosla, as mentioned, is a Silicon Valley veteran. Khosla and his team ran KiOR like a tech startup. In Silicon Valley, startups can create products and then scale and grow them quickly. Engineers are easy to find. Code is relatively quick to write. Khosla thought that he could use that same strategy at KiOR. He hired a bunch of people, wrote a business plan, and prepared for an IPO, long before the company had ever produced any fuel and long before they knew if the technology even worked, let alone could scale the way they intended. The growth strategy of companies like Airbnb and Snapchat is completely different than inventing a whole new fuel to power vehicles.

Still, KiOR raised $150 million with the IPO. It wasn't as much as Khosla was hoping for, but it was a start. In the beginning (late 2010 and early 2011), KiOR seemed to be on to something. In May of 2011, they held a grand groundbreaking ceremony at the former paper mill in Columbus. Local politicians wore hard hats and posed with shovels. The governor of Mississippi called KiOR a "game changer."

In KiOR's IPO documents, the company stated that they had achieved a significant milestone: they claimed they were able to turn one ton of biomass into 67 gallons of fuel. At that production level, KiOR would have been able to compete with traditional gasoline companies, like Chevron, and undercut their prices. They estimated the biofuel would cost $1.80 a gallon. During 2012 investor calls, KiOR's CEO said the company expected to be on track for 72 gallons in the future and aimed to get to 92 per one ton of wood chips – but none of this was actually true. The company had grossly overstated their production capabilities. KiOR's COO accused the company of cooking the books and resigned.

While all this drama was unfolding within KiOR, its stock was still trading higher and Khosla took two more of his biofuel companies public.

In November 2012, KiOR announced that it had made its first biofuel in Columbus. The company then set a target of between 500,000 and one million gallons before the end of the fiscal year.

That is not how it turned out, however. There were a ton of production problems. The conveyor belt that delivered wood chips was often broken. Other parts of the machinery were clogged with tar. KiOR spent tens of millions of dollars more than it expected, and still the staff couldn't solve the problems.

In early 2013, KiOR announced that it had not shipped any biofuel in 2012. However, by March 2013, KiOR's CEO was telling investors that although he was disappointed that they missed their 2012 targets, the company had solved their unexpected startup issues and shipped its first commercial biofuel just the day before. By May, KiOR was claiming the company was on track for three to five million gallons in 2013. By August of that year, KiOR had to admit that its actual output was 75% below its minimum target goal.

Finally, towards the end of 2013, KiOR began really unraveling. Condoleeza Rice resigned from the board. KiOR was hit with a securities class-action lawsuit. The CFO resigned. KiOR stock dropped 90% from its IPO price. Then, in March 2014, the company revealed it had been subpoenaed by the SEC, and as a result, had to admit its future was uncertain.

Khosla wasn't ready to give up. He tried to prop up the company by announcing $100 million in equity commitments from a number of investors, including Bill Gates. That just gave false hope to both KiOR's investors and employees. The problems continued and KiOR soon closed the plant.

With the plant shut down, no money coming in from fuel sales, and a loan payment coming due, KiOR quickly ran out of both time and money. Khosla shopped for a buyer, but was unsuccessful. In November of 2014, KiOR filed for bankruptcy, listing assets of $58.3 million. During the factory's brief time in operation, expenses were more than $600 million, but it produced only $2.3 million in revenue.

The fact is, to date, no biofuel startups have managed to create a next-generation biofuel on a commercial scale in the U.S. The startup costs are astronomical, and the lead times too long, to make it viable. Falling oil prices have only served to make the process even more difficult to undertake.

In 2015, less than two million gallons of cellulosic biofuel were produced in the U.S. That's far from the three billion gallons the EPA predicted would be produced in 2007. Just four biofuel plants have been built in the U.S. and all of them were built by mega-corporations, including DuPont. From this point of view, KiOR actually accomplished something extraordinary: it made nearly a million gallons of cellulosic fuel in a year.

Today, the list of biofuel startups backed by Khosla Ventures reads like a string of failures. Most of them have shut down, been sold off for pennies on the dollar, diversified, or moved into making bio-based materials and chemicals. Khosla believes the cost of his failures in this arena are justified, when you consider the benefits of biofuel to the planet.

During the summer of 2015, a judge approved KiOR's Chapter 11 plan. The company sold itself to an affiliate of Khosla's, trading $15 million in debt for equity. KiOR also received exit financing in the amount of $29 million. This enables KiOR and its 70 employees at its Texas headquarters to continue their research on how to make its biofuels on a larger scale.

KiOR's litigation is likely to drag on for years. However, Khosla is still a believer in the technology, as evidenced by his purchase of the remnants of KiOR. Will Khosla's biofuel dreams rise from the ashes of the KiOR disaster? Only time will tell.

/2016/05/GettyImages-180366422.jpg)

/2017/09/GettyImages-495486474.jpg)

/2018/09/GettyImages-850159670.jpg)

/2016/12/kevin-durant.jpg)

/2010/05/Peter-Thiel.jpg)

/2013/10/jeff-skoll.jpg)

/2019/11/GettyImages-1094653148.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2015/09/GettyImages-476575299.jpg)

:strip_exif()/2009/09/P-Diddy.jpg)

/2009/09/Brad-Pitt.jpg)

/2020/01/lopez3.jpg)

/2009/09/Cristiano-Ronaldo.jpg)

/2020/02/Angelina-Jolie.png)

/2019/04/rr.jpg)

/2017/02/GettyImages-528215436.jpg)

/2009/11/George-Clooney.jpg)

/2020/06/taylor.png)

/2019/10/denzel-washington-1.jpg)

/2020/04/Megan-Fox.jpg)

/2018/03/GettyImages-821622848.jpg)

/2009/09/Jennifer-Aniston.jpg)