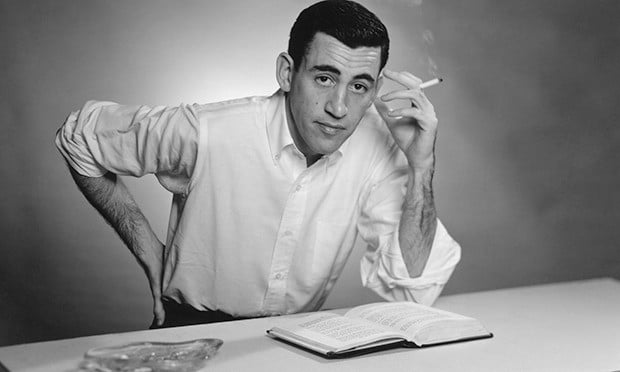

What Was J.D. Salinger's Net Worth?

J.D. Salinger was an American author who had a net worth of $20 million at the time of his death in 2010. J.D. Salinger was best known for his 1951 novel "The Catcher in the Rye," which sold 65 million copies, and the reclusive lifestyle he led after its publication. To this day, many decades after its first publication, "The Catcher in the Rye" still sells hundreds of thousands of copies per year. Other works of his include "Nine Stories," "Franny and Zooey," and a volume containing his novellas "Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters" and "Seymour: An Introduction." Salinger's final work, "Hapworth 16, 1924," was published in "The New Yorker" in 1965.

Early Life and Education

Jerome David Salinger was born on January 1, 1919, in Manhattan, New York. He was the second of two siblings. His father, Sol, came from a Jewish family of Lithuanian descent, while his mother, Marie, was of Scottish, Irish, and German heritage. In 1932, when the family moved to Park Avenue, Salinger began attending the private McBurney School. Despite struggling to fit in, he wrote for the school paper, appeared in plays, and managed the fencing team. Later, when his parents enrolled him at Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne, Pennsylvania, J.D. honed his literary skills by writing stories under the covers at night. He participated in a number of clubs while there and was the literary editor of the class yearbook. Upon graduating in 1936, he enrolled at New York University but dropped out the following spring.

In 1938, Salinger briefly attended Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pennsylvania, before leaving after one semester. The next year, he enrolled at Columbia University, where he was in a writing class taught by the editor of Story Magazine, Whit Burnett. Impressed by the young writer's work, Burnett accepted Salinger's short story "The Young Folks" for publication in the magazine; it was published in 1940. Following this, Burnett became Salinger's mentor and frequent correspondent.

World War II

In 1941, Salinger started submitting short stories to "The New Yorker. After rejecting seven of his stories, the paper finally accepted "Slight Rebellion off Madison," which introduced the character of Holden Caulfield. However, due to the attack on Pearl Harbor that occurred soon after, "The New Yorker" decided not to go through with publication (the story would later appear in the magazine in 1946). In 1942, J.D. was drafted into the army as part of the 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. He was present on D-Day, as well as at the Battle of the Bulge. During the war, Salinger met with one of his greatest influences, Ernest Hemingway, who was serving as a war correspondent in Paris.

Later, J.D. was assigned to a counter-intelligence unit, and he used his fluency in German and French to interrogate POWs. In 1945, he earned the rank of Staff Sergeant. He continued to write while on duty, publishing a number of stories in magazines, including "Collier's" and "The Saturday Evening Post." After serving in five campaigns, Salinger was briefly hospitalized for combat stress reaction.

"The Catcher in the Rye"

Following the defeat of Germany, Salinger enlisted in the Counterintelligence Corps to help with the denazification of the country. In 1947, back at home, he submitted his short story "The Bananafish" to "The New Yorker." After the magazine asked him to give it some more time, he spent a year revising the story with the editors; it was finally published in 1948. The story became the first of seven by Salinger to feature the Glasses, a fictional family headed by two retired vaudeville stars.

In 1951, J.D. released his most famous and influential work, "The Catcher in the Rye." The novel follows the experiences of its sulky 16-year-old narrator, Holden Caulfield, who bristles against the phoniness he perceives in the adult world. Although initial critical reactions to the book were mixed, "The Catcher in the Rye" quickly became a success; it was reprinted eight times within two months of its publication and spent 30 weeks on the "New York Times" bestseller list. Due to its frank and often crude language, the novel was met with disapproval by many groups and was banned or censored in many countries and US schools.

San Diego Historical Society/Getty Images

Later Writing and Reclusion

In 1953, Salinger published "Nine Stories," which consisted of seven stories he wrote for "The New Yorker" and two others the paper had rejected. It received fairly positive reviews and spent three months on the "New York Times" bestseller list.

As notoriety around "The Catcher in the Rye" grew, Salinger gradually retreated from the public eye. In 1953, he moved to Cornish, New Hampshire, and began publishing with less frequency, only releasing four more stories through the end of the decade. In 1961, he published "Franny and Zooey," and in 1963 released "Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction." Both of these volumes contained short stories and novellas originally published in "The New Yorker" between 1955 and 1959. Finally, in 1965, J.D. released his final work: the epistolary novella "Hapworth 16, 1924," which was widely panned. Fed up with the publication process, Salinger continued to write regularly for his own pleasure, never releasing his manuscripts.

Personal Life and Legal Battles

Soon after his postwar service in Weißenburg, Germany, J.D. married Sylvia Welter. Eight months after he brought her to the US, their marriage fell apart, and Welter returned to Germany. Salinger's second marriage came in 1955 to Radcliffe student Claire Douglas; they had two children, Margaret and Matthew. Their marriage was fraught with discord over their opposing religious beliefs, as Salinger had switched between everything from Advaita Vedanta Hinduism to Dianetics. Claire also felt that her husband had more affection for their sickly daughter Margaret than for her. The two divorced in 1966. In 1972, when he was 53, Salinger carried out a nine-month relationship with 18-year-old writer Joyce Maynard. Later, in the 1980s, J.D. was involved with actress Elaine Joyce and then with nurse Colleen O'Neill, whom he married.

Despite his attempts to avoid public exposure, a number of copyright lawsuits drew Salinger to the media's attention. In 1986, the author sued to stop the publication of a biography that made robust use of letters he wrote to acquaintances; the court ruled in his favor. Later, in 1998, J.D. had his lawyers block a screening of the Iranian film "Pari," which loosely adapted "Franny and Zooey." In 2009, the author prevented the US publishing of an unauthorized sequel to "The Catcher in the Rye." Due to the botched Hollywood treatment of one of his short stories in the 1940s, Salinger forever prohibited film adaptations of his work.

Death and Legacy

On January 27, 2010, at the age of 91, Salinger passed from natural causes at his home in New Hampshire. In 2019, his widow Colleen O'Neill and son Matthew announced that, at some point in the future, all of Salinger's unpublished manuscripts would be shared with the public.

Salinger's influence runs far and wide. His writing has inspired such authors as Susan Minot, Harold Brodkey, Haruki Murakami, Joel Stein, Jonathan Safran Foer, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelists John Updike and Philip Roth. The legacy of "The Catcher in the Rye" also continues to be prolific, with worldwide sales of over 10 million copies. One of the most frequently taught books in schools, it was included on "Time" magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923.

/2013/09/JD-Salinger-portrait-New-010.jpg)

/2014/04/Matt-Salinger.jpg)

/2017/08/Joyce-Maynard.jpg)

/2024/01/Kurt-Vonnegut2.jpg)

/2022/09/nora-roberts.jpg)

/2022/07/hemingway.jpg)

/2021/10/John-Boyega.jpg)

/2010/11/josh.jpg)

/2022/05/Nayib-Bukele.jpg)

/2010/11/russell-armstrong.png)

/2013/07/courtney-henggeler.jpg)

/2021/12/Lauren-Sanchez.jpg)

/2020/10/cate.jpg)

/2018/04/GettyImages-942450576.jpg)

/2021/08/bert-kreisher.jpg)

/2021/09/tom-segura.jpg)

/2023/09/john-mars.png)

/2013/09/JD-Salinger-portrait-New-010.jpg)

/2014/04/Matt-Salinger.jpg)

/2018/07/GettyImages-487892375.jpg)

/2022/09/Truman-Capote.jpg)

/2022/09/nora-roberts.jpg)

/2012/07/Mary-Higgins-Clark-e1580530409588.jpg)

/2018/01/mario.jpg)

/2010/12/Jonathan-Franzen.jpg)